After writing a considerable number of SQL scripts, you’re likely to reach some form of a plateau in terms of performance. You extract insights using the same strategies and run into the same types of errors.

Fortunately, you can improve your experience with writing queries by taking the time to understand how the clauses in SQL are evaluated.

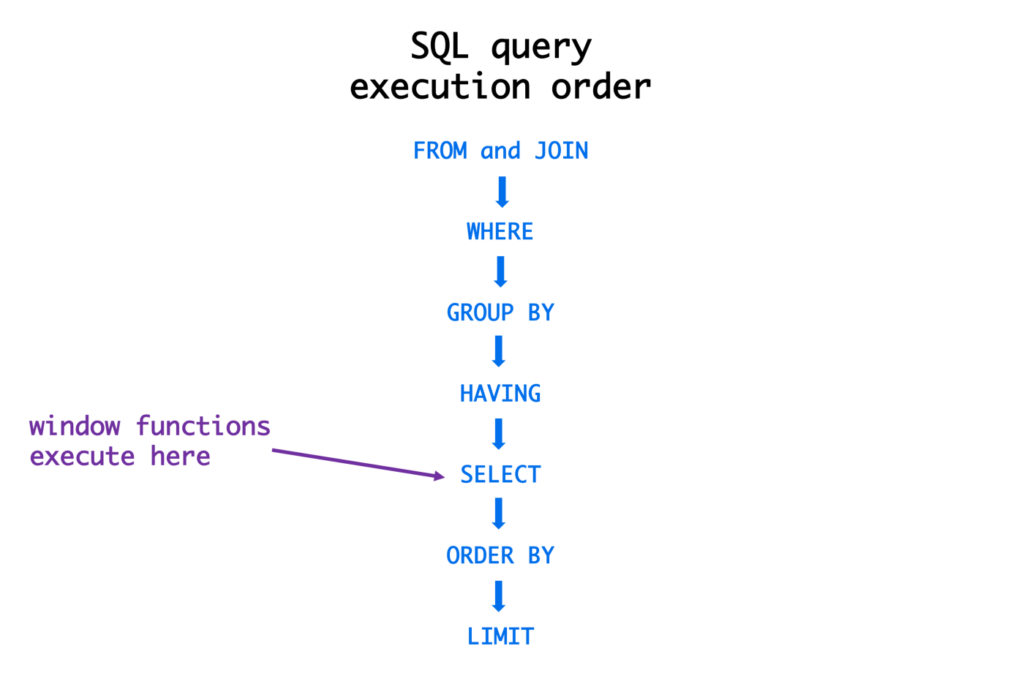

Here, we discuss the order of execution in SQL and explain why it matters.

We can now talk about how they all fit together in the context of a complete query.

Example Query:

SELECT DISTINCT column, AGG_FUNC(column_or_expression), …

FROM mytable

JOIN another_table

ON mytable.column = another_table.column

WHERE constraint_expression

GROUP BY column

HAVING constraint_expression

ORDER BY column ASC / DESC

LIMIT count OFFSET COUNT ;

Each query begins with finding the data that we need in a database and then filtering that data down into something that can be processed and understood as quickly as possible. Because each part of the query is executed sequentially, it’s important to understand the order of execution so that you know what results are accessible where.

Query Order of Execution

1. FROM and JOINs

The FROM clause, and subsequent JOINs are first executed to determine the total working set of data that is being queried. This includes subqueries in this clause, and can cause temporary tables to be created under the hood containing all the columns and rows of the tables being joined.

2. WHERE

Once we have the total working set of data, the first-pass WHERE constraints are applied to the individual rows, and rows that do not satisfy the constraint are discarded. Each of the constraints can only access columns directly from the tables requested in the FROM clause. Aliases in the SELECT part of the query are not accessible in most databases since they may include expressions dependent on parts of the query that have not yet executed.

3. GROUP BY

The remaining rows after the WHERE constraints are applied are then grouped based on common values in the column specified in the GROUP BY clause. As a result of the grouping, there will only be as many rows as there are unique values in that column. Implicitly, this means that you should only need to use this when you have aggregate functions in your query.

4. HAVING

If the query has a GROUP BY clause, then the constraints in the HAVING clause are then applied to the grouped rows, discard the grouped rows that don’t satisfy the constraint. Like the WHERE clause, aliases are also not accessible from this step in most databases.

5. SELECT

Any expressions in the SELECT part of the query are finally computed.

6. DISTINCT

Of the remaining rows, rows with duplicate values in the column marked as DISTINCT will be discarded.

7. ORDER BY

If an order is specified by the ORDER BY clause, the rows are then sorted by the specified data in either ascending or descending order. Since all the expressions in the SELECT part of the query have been computed, you can reference aliases in this clause.

8. LIMIT / OFFSET

Finally, the rows that fall outside the range specified by the LIMIT and OFFSET are discarded, leaving the final set of rows to be returned from the query.

Conclusion

Not every query needs to have all the parts we listed above, but a part of why SQL is so flexible is that it allows developers and data analysts to quickly manipulate data without having to write additional code, all just by using the above clauses.

Feel free to use the comment box below, in case you have any queries.