The frontiers separating regions have evolved over time are still changing. What we understand as regional cultures today are often the product of complex processes of intermixing of local traditions with ideas from other parts of the subcontinent. In this post, let us quickly go through some of the regional cultures of India during the medieval period.

Kerala: The Cheras and Malayalam

- The Chera kingdom of Mahodayapuram was established in the 9th century in the south-western part of the peninsula, part of present-day Kerala.

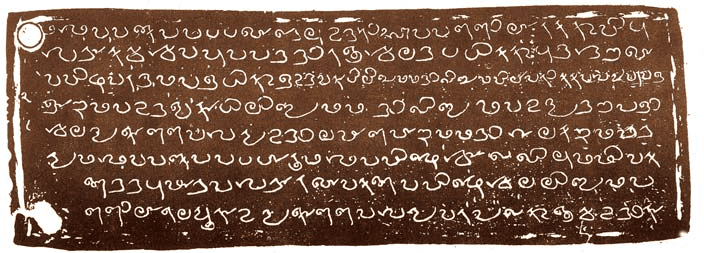

- It is likely that Malayalam was spoken in this area.

- The rulers introduced the Malayalam language and script in their inscriptions. This development is considered as one of the earliest examples of the use of a regional language in official records in the subcontinent.

- At the same time, the Cheras also drew upon Sanskritic traditions. A 14th-century text, the Lilatilakam, dealing with grammar and poetics, was composed in Manipravalam – literally, “diamonds and corals” referring to the two languages, Sanskrit, and the regional language.

Orissa: The Jagannatha Cult

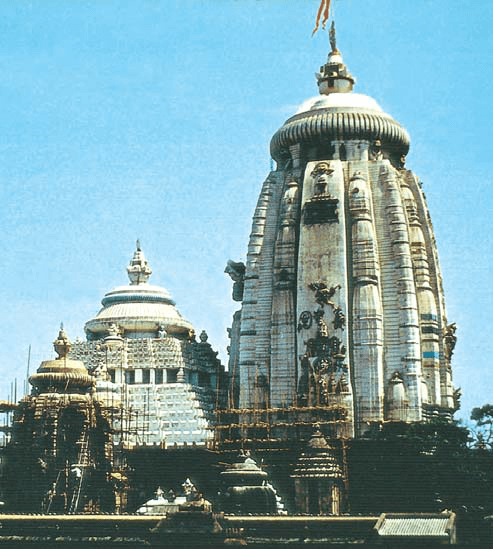

- In some areas, regional cultures grew around regional traditions eg: Jagannatha cult of Puri (Odisha).

- As the temple gained in importance as a center of pilgrimage, its authority in social and political matters also increased.

- Mughals, Marathas, English East India Company all attempted to gain control over the temple because it could make rule acceptable to local people.

Rajastan: The Rajputs

- The Rajputs are often recognised as contributing to the distinctive culture of Rajasthan.

- Rulers like Prithviraj cherished the ideal of the hero who fought valiantly, often choosing death on the battlefield rather than face defeat.

- Women are also depicted as following their heroic husbands in both life and death – there are stories about the practice of sati.

The Story of Kathak

- Dance form Kathak was originally a caste of storytellers in temples of north India.

- Kathak began evolving into a distinct mode of dance in the 15th and 16th centuries with the spread of the bhakti movement.

- The legends of Radha-Krishna were enacted in folk plays called rasa lila, which combined folk dance with the basic gestures of the kathak story-tellers.

- During Mughal period Kathak acquired a distinctive style which is still followed today.

- Kathak, like several other cultural practices, was viewed with disfavour by most British administrators in the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Recognised as one of “classical” forms of dance in the country after independence.

Miniature Paintings

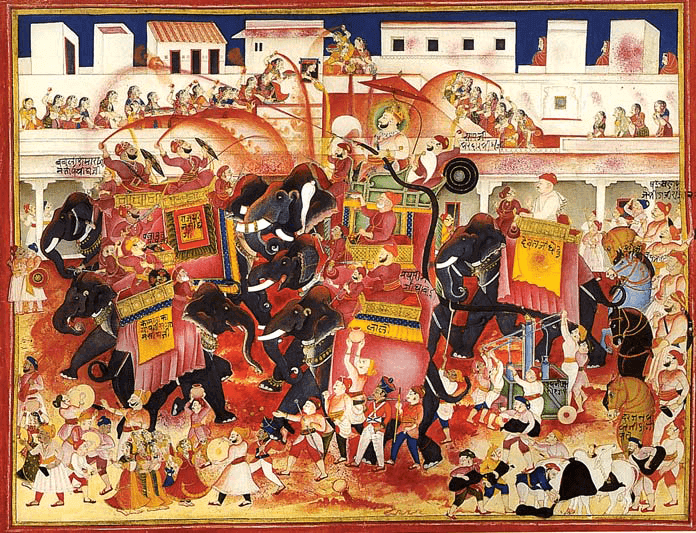

- As the name suggests, small-sized paintings, generally done in watercolor on cloth or paper.

- Some of these are found in Western India which was used to illustrate Jaina texts.

- With the decline of the Mughal Empire, many painters moved out to the courts of the emerging regional states.

- As a result, Mughal artistic tastes influenced the regional courts of the Deccan and the Rajput courts of Rajasthan.

- Portraits of rulers and court scenes came to be painted, following the Mughal example.

- Himalayan foothills attracted miniature painting which is known as “Basohli”.The most popular text to be painted here was Bhanudatta’s Rasamanjari.

- Kangara school of paintings got inspiration from Vaishnavite traditions. Soft colors including cool blues and greens and a lyrical treatment of themes distinguished Kangra painting.

Bengal: Language and Literature

While Bengali is now recognised as a language derived from Sanskrit, early Sanskrit texts (mid-first millennium BCE) suggest that the people of Bengal did not speak Sanskritic languages. How, then, did the new language emerge?

From the fourth-third centuries BCE, commercial ties began to develop between Bengal and Magadha (south Bihar), which may have led to the growing influence of Sanskrit. During the fourth century the Gupta rulers established political control over north Bengal and began to settle Brahmanas in this area. Thus, the linguistic and cultural influence from the mid-Ganga valley became stronger.

From the eighth century, Bengal became the centre of a regional kingdom under the Palas. Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, Bengal was ruled by Sultans who were independent of the rulers in Delhi. In 1586, when Akbar conquered Bengal, it formed the nucleus of the Bengal suba. While Persian was the language of administration, Bengali developed as a regional language.

By the fifteenth century the Bengali group of dialects came to be united by a common literary language based on the spoken language of the western part of the region, now known as West Bengal.Thus, although Bengali is derived from

Thus, although Bengali is derived from Sanskrit, it passed through several stages of

evolution. Also, a wide range of non-Sanskrit words, derived from a variety of sources including tribal languages, Persian, and European languages, have become part of modern Bengali.

Early Bengali literature may be divided into two categories – one indebted to Sanskrit and the other

independent of it.

The first includes translations of the Sanskrit epics, the Mangalakavyas (literally

auspicious poems, dealing with local deities) and bhakti literature such as the biographies of

Chaitanyadeva, the leader of the Vaishnava bhakti movement.

The second includes Nath literature such as the songs of Maynamati and Gopichandra, stories

concerning the worship of Dharma Thakur, and fairy tales, folk tales and ballads. The Naths were ascetics who engaged in a variety of yogic practices.

Pirs and Temples

Pirs were community leaders, who also functioned as teachers and adjudicators and were sometimes ascribed with supernatural powers.

The early settlers in eastern India sought some order and assurance in the unstable conditions of the new settlements. This was provided by Pirs.

The term ‘Pirs’ included saints or Sufis and other religious personalities, daring colonisers and deified soldiers, various Hindu and Buddhist deities and even animistic spirits. The cult of pirs became very popular and their shrines can be found everywhere in Bengal.

Bengal also witnessed a temple-building spree from the late fifteenth century, which culminated in the

nineteenth century. Many of the modest brick and terracotta temples in Bengal were built with the support of several “low” social groups, such as the Kolu (oil pressers) and the Kansari (bell metal workers).

When local deities, once worshipped in thatched huts in villages, gained the recognition of the Brahmanas, their images began to be housed in temples. The temples began to copy the double-roofed (dochala) or four-roofed (chauchala) structure of the thatched huts.

Bengal: Fish as food

Bengal is a riverine plain which produces plenty of rice and fish. Understandably, these two

items figure prominently in the menu of even poor Bengalis.

Brahmanas were not allowed to eat nonvegetarian food, but the popularity of fish in the local diet made the Brahmanical authorities relax this prohibition for the Bengal Brahmanas. The Brihaddharma Purana, a thirteenth-century Sanskrit text from Bengal, permitted the local Brahmanas to eat

certain varieties of fish.